Introduction

So you’ve learned about why sustainable investing is key to solving climate change. And you’ve seen why it matters which stocks and bonds you hold in places like your retirement account. What can you expect in performance terms by aligning your portfolio with solving climate change?

Let’s start by looking backward.

Historical Performance of Sustainable, Socially Responsible, and ESG Investing

Over the Last 30+ Years, Your Portfolio Would Have Been Better off Without Fossil Fuel Stocks

When it comes to fossil fuels, investment advisors have often called them a necessary evil in a balanced portfolio. That removing them will hurt long-term performance.

Maybe that was true 60 years ago. But not over the past 30. From 1989 to 2021, the S&P 500 would have performed better without fossil fuel stocks. The energy index performed particularly poorly during the 2010s, while the S&P 500 and stock market had one of its best-ever decades.

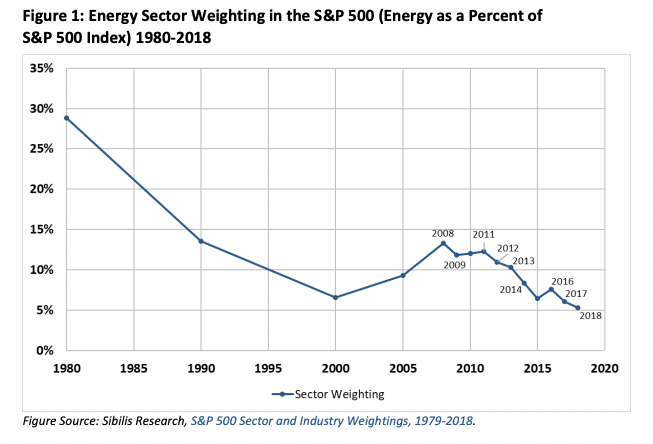

Fossil fuel stocks’ prominence on the stock market has changed considerably. In 1980, 29% of the market capitalization of the S&P 500 (the 500 largest companies on US stock exchanges) were fossil fuel companies. As of the writing of this piece in February 2022, it represented just 3.52%.

Fossil fuel stocks being critical to long-term portfolio performance has clearly not shown itself to be true over the past three decades. So what about the next three?

Fossil Fuel Future Performance Outlook

Over the Next 30 Years, Fossil Fuels Are Poised for a Significant Decline (And May Already Be a Bubble)

Maybe fossil fuel stocks had a bad 30 years. But maybe that just means their price is low, and now is a good time to buy? Looking ahead, what can we expect over the next 30 years for the fossil fuel industry?From an investment perspective, it’s not promising. Altruistically, there is a growing global consensus that this industry must decline.

To remain below 1.5ºC of warming, the fossil fuel industry will need to contract by ~75% from now until 2050. Each new climate change-driven record-setting milestone adds more pressure for individual, corporate, and government action to accelerate this transition.

Even without government intervention, this transition is underway, driven by sheer market forces. Fossil fuels are starting to lose their market share to zero-carbon competitors because technologies like solar, wind, batteries, and electric cars make better financial sense.

Some even argue that fossil fuels are in a bubble. It’s a debt-heavy, very capital-intensive industry. If the price of oil or natural gas drops too far or too much of their margin is needed to pay an escalating carbon tax (or a carbon tariff, like the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism), thousands of sites around the globe will no longer be financially viable. No investor wants to be left with those kinds of stranded assets.

Future Performance of Sustainable Investing

Over the Next 30 Years, Climate Solutions Are Poised for Significant Growth (And May Eat Fossil Fuels’ Lunch)

In 2009, installing solar panels would have been the most expensive way to generate electricity. In 2020, costs had fallen so much that panels have become the cheapest method. Wind isn’t far behind.

Annual global large-scale battery cell production went from 64 GWh in 2016 to 613 GWh in 2020 (a whopping 77% CAGR).

Electric cars are faster, safer, more powerful, and roomier than gas-powered ones. As of 2021, they reached lifetime cost-parity with fossil-fuel-powered cars (electric cars are much cheaper to maintain). And they are projected to reach upfront cost-parity with them by 2027.

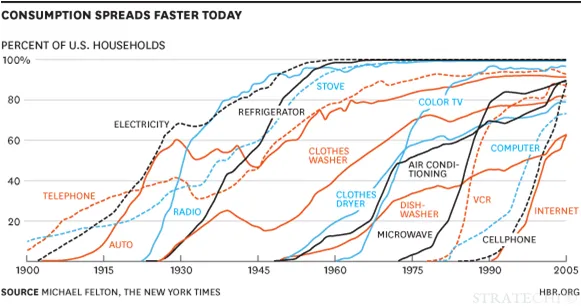

From computers to telecoms to the internet, it’s historically paid off to invest early in young, fast-growing industries. The core climate-solutions technologies that are ready to seriously scale are still at the beginning of their growth curves. And the more they grow, the fewer customers fossil fuel companies have.

Historical Underperformance of Fossil Fuels

1989 - 2021: Fossil Fuel Stocks Underperformed

Fossil fuels stocks have often been seen as a necessary part of a balanced, modern portfolio. Regardless of how you feel about them, investment professionals have argued that fossil fuel stocks’ importance to the global economy, tied with their lower correlation with the rest of the stock, made it critical to include them.

And that is certainly true. There have been times when fossil fuel stocks have significantly outperformed the overall market.

This happened in my lifetime (I was born in 1989). During the 2000s, or the "lost decade" as it is sometimes called in the investment world, the S&P 500 in BLUE was significantly outperformed by the US Energy Index in GREEN (January 1, 2000 to December 31, 2010).

If the investment professionals are correct, we would expect counter-cyclical performances of the Energy Index like this to translate into better performance for non-divested portfolios, right?

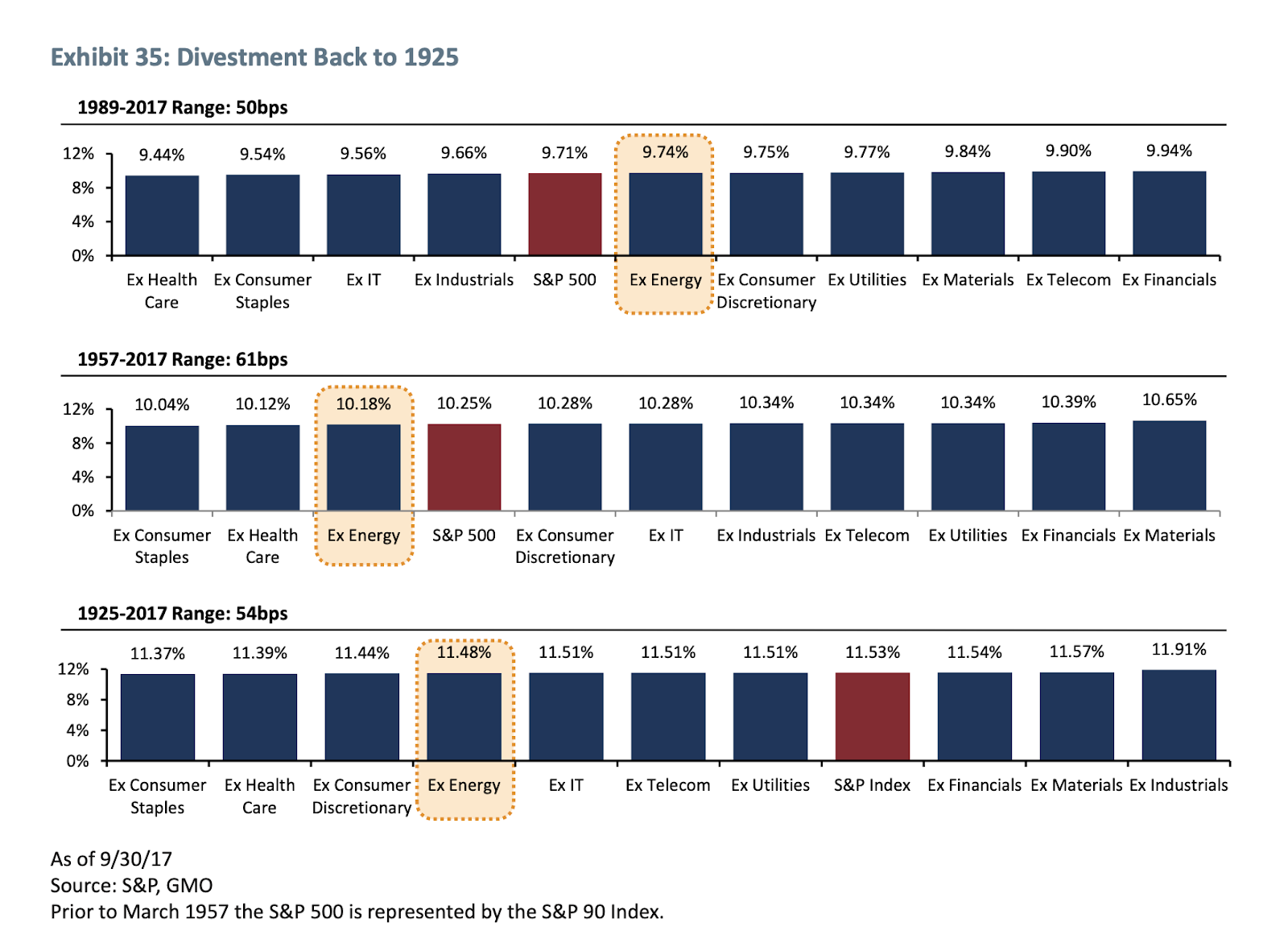

We have some good data for this. Jeremy Grantham, the founder of the very famous asset management firm GMO, looked at how the S&P 500 would have performed with various sectors removed. You can read the full piece in his 2018 report, The Race of Our Lives Revisited, looking at the major macro trends that should keep investors (and all of us) up at night.

Here’s GMO’s data on fossil fuel divestment:

If we go back to 1925, it looks like those investment managers may have a point, albeit a slight one. From 1925 to 2017, the S&P 500 without fossil fuels would have performed on average 0.05% worse per year than a portfolio with energy stocks.

But the opposite was true from 1989 to 2017. The first graph we showed, the one from 2000 to 2010 where the Energy Index outperformed the S&P 500 by more than 3x, is right smack in the middle of this timeframe. If fossil fuels were necessary for long-term performance, wouldn’t a portfolio divested from fossil fuels perform worse with containing such a decade?

Yet the S&P 500 divested of fossil fuel stocks performed 0.03% better per year from 1989 to 2017 than the overall S&P 500.

And the disparity has only grown since GMO calculated this data. Here’s the performance data from 09/30/17 to 02/10/22 (the date we’re writing this article). The S&P 500 is in BLUE and the US Energy Index is in GREEN

Over the past five years (02/10/17 to 02/10/22), the S&P 500 has averaged an annual return of 16.32%, while the Energy Index averaged only 2.86%, meaning that from 1989 to early 2022, a divested S&P 500 probably performed even more than 0.03% better annually than one with fossil fuel stocks in it.

The whole reason you diversify a portfolio is long-term performance. Diversification helps protect your portfolio during downtimes. It pays to have eggs in more baskets. But that’s clearly not always true. While fossil fuels did have a period of significant outperformance during the 2000s, you would have been better off without them over a more zoomed-out period.

We’ll leave you with this. In 1980, the fossil fuel industry represented over 29% of the S&P 500 by market capitalization. As of the most recent data we found in writing this article (February 4, 2022), it now represents 3.52%.

Fossil fuels are an industry in decline, and they have been for a long time.

Why Fossil Fuel Stocks are Likely to Continue Underperforming

As we explored previously, looking backward, including fossil fuels in the S&P 500 would have led to worse performance from 1989 to 2021 than one divested from them.

So what about looking ahead? Was that period anomalous or the beginning of a larger trend? If you’re saving for retirement or some other long-time horizon goal, will you be better off with or without fossil fuel stocks in your portfolio?

To us, it’s hard to see a case for why fossil fuels make sense as a long-term investment. Put simply, they are an industry in decline.

Even without any government action around climate change, fossil-fuel-free technologies like electric cars, renewable energy, battery storage, and electric heat pumps are poised to replace a significant portion of their end market share. Based on economic forces alone, far fewer cars will require gasoline, and fewer power plants will demand coal in 20 years.

These technological shifts make it dangerous not only to hold the stocks and bonds of fossil fuel companies but also those of the major banks that fund their expansion.

And all of this is the case without any major governmental action on climate change. Relatively straightforward governmental actions, such as ending fossil fuel subsidies, would accelerate these trends. More complicated ones, such as implementing a carbon tax and enforcing emission-free electricity generation standards, would dramatically increase them and push fossil fuels out of all sectors of the economy.

So let’s dig into the data by first seeing where fossil fuels are used in the economy and where emission-free technologies outperform them.

Oil: 36.66% Of the Oil Used Today Is for Light Duty Cars and Trucks. Electric Cars Are Better, Cheaper, Faster, & Safer

ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP’s primary source of revenue is oil. Quick quiz: which area of the economy uses the most of its products?

- Airplane fuel

- Cars and trucks

- Plastics

- Long-haul big rigs

- The military

If we use the US as an example and data from the EIA, it’s cars and trucks by a landslide. Yep, the kind sitting in your driveway. Figures show that 66% of the petroleum consumed in the US goes into transportation, and 55.5% of the energy used in transportation was used by light-duty vehicles, which, according to the EIA, comprise "passenger cars, pickup trucks, vans, sport utility vehicles, and crossover vehicles."

Imagine if there was a technology that made light-duty vehicles faster, more powerful, roomier, safer, and increased the lifetime of a car from something like 250k miles to over 1m miles without using oil. Imagine if that technology was mature enough that switching to it made economic sense over the vehicle’s lifetime (due to the lower maintenance costs). And imagine if, given these multiple benefits, global production scales up to put this technology on a path to cost the same or even cheaper than oil-powered cars in the next five years.

If all oil-powered light-duty vehicles were swapped out with this technology overnight, the demand for oil in the US would drop by 36.6% (66% * 55.5%). And that technology is here. Electric cars are not something just for environmentalists. They are simply better cars. They are better trucks. Electric cars have around 20 moving parts. Gas-powered cars have hundreds.

Police forces around the country are switching their fleets to Tesla Model Y electric vehicles. Even though they cost more than gas-powered cars upfront, the lower fuel price and maintenance costs and much longer lifetime lead to an average payback of 6-18 months. Law enforcement is already making the switch today, with current higher prices for electric cars. In five years, as the cost of electric cars falls even further, the math for making this kind of switch will become even more obvious.

And that’s just for light-duty vehicles. About 16% of the oil used in the US is by medium- and heavy-duty trucks (the long-haul kind). While they are not as commercially ready to scale than electric cars, electric- and hydrogen-powered trucks similarly promise better economics. They can go farther without refueling, refuel more cheaply, require less maintenance, and run longer.

While this transformation will not happen overnight, shifts from an inferior to a superior tech accelerate at surprising, often exponential speeds. These classic "S" curve adoption patterns of new technologies are happening faster than ever.

In 2030 and especially by 2035, our roads and highways will likely be looking (and sounding) far different than they do today. And far less oil will be used in the process.

Before moving to the next section, the following shows the total oil each of these sectors uses in the US:

- Airplane fuel: 5.3%

- Cars and trucks: 36.7%

- Plastics: 7.4% (this data is harder to find, but it’s ballpark correct. If anything, it’s a little high)

- Long-haul big rigs: 16.1%

- The military: 1.3%

Coal: 91% Of the Coal Used Today Is for Electricity. Solar and Wind Are Cheaper. Batteries Make Them Even Better

While some coal is used in making steel and cement, the vast majority of coal extracted today will be burned to generate electricity. In the US, according to the EIA, 91.4% of coal consumed is used to make electricity.

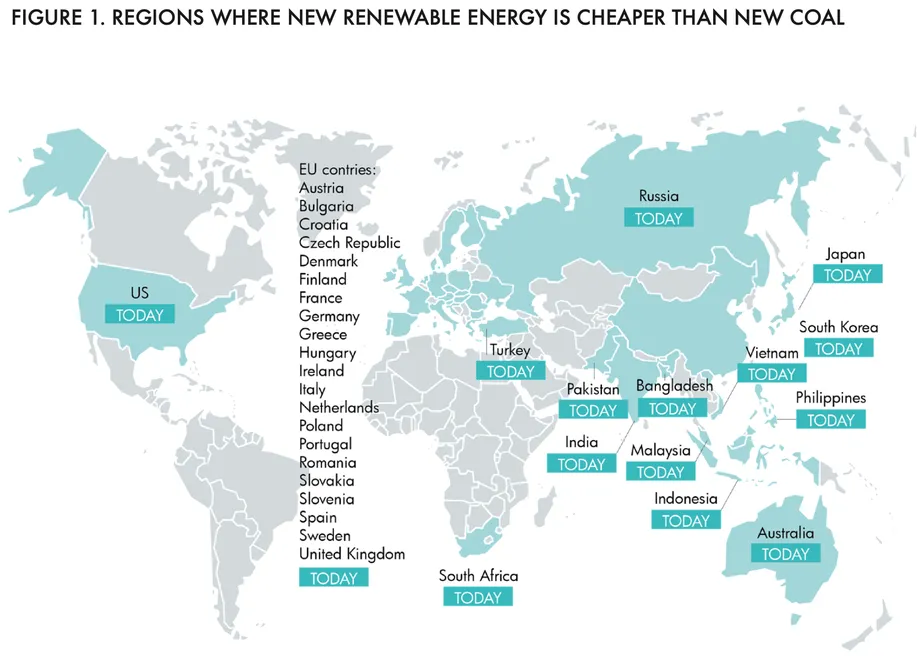

And the problem for coal companies, from those mining it to shipping it to burning it, is that the economics of using coal to generate electricity don’t really pencil out anymore. Especially when compared to renewables.

Some headlines:

- Vox (2020): Four Astonishing Signs of Coal’s Declining Economic Viability: Coal is Now a Loser Around the World

"The results reveal that in the US and across the world, coal power is dying. By 2030, it will be uneconomic to run existing coal plants. That means all the dozens of coal plants on the drawing board today are doomed to become stranded assets." - IRENA (2020): Renewables Increasingly Beat Even Cheapest Coal Competitors on Cost

"Renewable power generation costs in 2019 show that more than half of the renewable capacity added in 2019 achieved lower power costs than the cheapest new coal plants… Replacing the costliest 500 GW of coal with solar PV and onshore wind next year would cut power system costs by up to USD 23 billion every year and reduce annual emissions by around 1.8 gigatons (Gt) of carbon dioxide (CO2), equivalent to 5% of total global CO2 emissions in 2019. It would also yield an investment stimulus of USD 940 billion, which is equal to around 1% of global GDP." - Carbon Tracker (2018): Powering Down Coal: Navigating the Economic and Financial Risks in the Last Years of Coal Power

"The myth of cheap coal – 35% of coal capacity costs more to run than building new renewables in 2018, increasing to 96% by 2030."

Source: Carbon Tracker

So why is the world still building coal plants? The Vox article above puts it very well:

"In the US and across the world, coal power is a dead man walking. It stumbles on because, though it has completely lost its economic advantage, it still retains considerable social and political power. It survives on sheer momentum, market distortions, long-established political relationships.

The tidal force of economics will erode those advantages eventually, but policymakers would be smart to use the current downturn, and the need for stimulus, as an occasion to hasten that transition."

Coal still has a lot of momentum behind it. China has the fourth-highest coal reserves. Russia has the second most. While they will only be able to prop up a failing business model for so long, they have reasons to do so that stem beyond economics.

And the economics are getting worse for coal. Its one saving grace versus renewables was that it was a "dispatchable" power source, meaning it could provide electricity 24/7, regardless of the weather. Utility-scale battery storage is here and ramping up quickly. Excess solar electricity generated during the day can be stored and then used at night.

The writing is on the wall for coal. While the music is still playing, the song is winding down. And as an investor, you don’t want to be the one left standing on the outside without a chair.

Natural Gas: 22.5% Of Natural Gas Is Used for Heating Homes/Buildings. Heat Pumps Are Cheaper (Especially When Paired With Cheap Renewable Electricity)

Of the three fossil fuels, natural gas seems the most entrenched in everyday use. From highest to lowest, here is a breakdown of natural gas usage in the US in 2021:

- Electricity: 38%

- Industrial: 33%

- Residential: 15%

- Commercial: 10%

- Transport: 3%

Unlike coal-fired electricity, the economics of natural gas-fired power plants still largely makes economic sense. While this could change with the swings in gas prices and government intervention (carbon tax, end of subsidies, and so on), it’s hard to see as clear a path to natural gas plants being shut down for economic reasons alone over the next 20 years (although if renewables and batteries continue to drop in cost, construction of new natural gas plants could decline far faster than anticipated).

Similarly, barring governmental interventions, the paths for replacing natural gas for industrial purposes are murkier. A little under half of the natural gas used in the US in 2018 for industrial purposes was by the chemical industry and involved processes harder to decarbonize at scale.

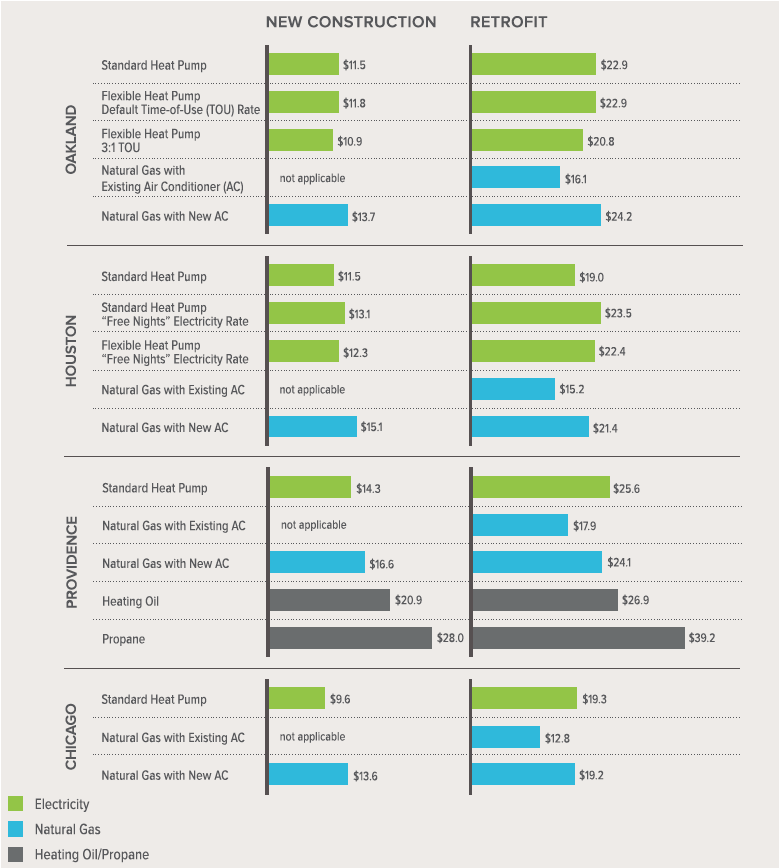

Natural gas is starting to get economically outcompeted in the arena of residential and commercial heating. In 2015, 67.6% of the natural gas used in houses/residences was for space heating (such as furnaces) and another 25.7% for heating water (source: EIA), meaning about 93% of natural gas usage in homes was for heating. In commercial buildings the figure is a little lower: 60% of natural gas for space heating and 18% for water heating, totaling 78.5%.

All told, if 15% of natural gas is used in homes and 93% of that percentage is for heating and 10% of that percentage is used in commercial buildings, with 78.5% in heating, space heating and heating water in buildings account for 22.5% of the natural gas usage in the US.

And in many, but not all, circumstances, switching to an electric heat pump makes economic sense. For any new construction, the economics pencil out far better for electric heat pumps over natural gas-powered systems. It also makes sense for some retrofits.

The Rocky Mountain Institute has done great work on this, looking at the 15-year cost comparison for electric heat pumps versus natural gas heating systems (reported in $ thousands):

The good news is that heat pumps have expanded their market share over the past few years both in the US and globally. According to the IEA, 40% of new single-family homes in the US have heat pumps, and 50% of multi-family units. In the EU, heat pump sales increased by 12.5% yearly from 2015 to 2020.

The bad news is that heat pumps still have a long way to go. Retrofitting a heat pump does not often make economic sense or takes many years to break even as an investment compared with a gas furnace in many areas. This situation will change: as heat pumps continue to scale, we can expect prices to continue dropping. As rooftop solar becomes more ubiquitous, the benefits of switching your home’s heating to much cheaper and home-generated electricity will also grow.

So, as you can see, while there is a clear economically-driven path to see a reduction in natural gas demand, it is the least clear of the three fuel types. Whereas we can expect economic forces to drive the decline in oil and coal demand, natural gas will likely not decline without some level of governmental intervention.

Won’t the Fossil Fuel Industry Just Make Up for These Declines by Expanding Elsewhere?

Oh, they’re trying to. It’s just hard to see where.

Oil. The headline of this Vox article says it all: "Big Oil’s hopes are pinned on plastics. It won’t end well: The industry’s only real source of growth probably won’t grow much." Oil doesn’t really have that many places it can turn to for growth, given that so much of its demand comes from the transportation industry.

Coal. Coal has even fewer prospects than oil to expand into new industries. Coal, the first fossil fuel, has slowly been replaced across the supply chain by oil and natural gas in everything but electricity generation and specific industrial processes (steel and cement). Barring something completely out of left field, it’s very unlikely that another market will arise for coal. Even with CCUS technology (more on that below), coal-fired electricity generation is already an underwater business model in many cases.

Natural Gas. Of the three, natural gas has the best prospects for market expansion and continued relevance, but it is heavily dependent on technological breakthroughs that haven’t happened yet. If Carbon Capture, Usage, and Sequestration (CCUS) technology can reach technical feasibility and economic scalability, natural gas could easily find a way to stick around in two areas. Firstly, it could continue as a source of electricity (with the excess carbon being captured and stored). Secondly, it could continue as a feedstock generating hydrogen. With the hydrogen economy expected to increase dramatically over the coming decades, this development could be significant. However, according to some estimates, like this one from Bloomberg, "green hydrogen" (made without fossil fuels) is projected to be the cheapest source of hydrogen by the end of the decade.

Any Government Intervention Will Only Hasten Fossil Fuels’ Decline

All of the potential declines in fossil fuel demand above are based on the financial superiority of their emission-free alternatives. Public and corporate pressure weigh the odds even further against the long-term viability of fossil fuels. Broadly, the government can do two things to accelerate fossil fuels’ decline:

Option 1: Incentivize Alternatives

The US government provides incentives to help renewable energy grow faster. Unfortunately, it’s only about 30% of what the fossil fuel industry received. There is significant pressure and momentum for this ratio to change. Much of Biden’s Build Back Better agenda focuses on providing incentives to deploy cleantech quicker.

Cities and municipalities are providing more rebates to make the switch from gas to heat pumps and induction stoves more economical. In the US and around the world, we will likely see increased governmental support for zero-emission alternatives like renewables, EVs, and green hydrogen.

Option 2: Make Fossil Fuels More Expensive (Or Ban Them)

Governments can also accelerate solving climate change (and the decline of fossil fuels) by making fossil fuels less viable than zero-emission alternatives. Things like carbon taxation and reducing fossil fuel subsidies can impact supply chains at a high level. Unfortunately, the fossil fuel industry has proven very effective at thwarting such political efforts. Where we have seen progress is in local contexts. Cities and municipalities around the US have passed natural gas bans on new construction.

While it is unclear how much worldwide backing there will be for the government’s support of the transition to a zero-carbon economy, we can be confident that more will come. And the more that does, the more it turns the economics against any hope of staving off decline, let alone growth for the fossil fuel industry.

Fossil Fuel Debt Could Be the Next Asset Bubble

We’ll end this piece here. Some economists argue that the market is not adequately preparing for the transition from fossil fuels and that the climate risk of investing in fossil fuels extends beyond their long-term decline. That banks are making loans based upon an expansion in fossil fuel use that is unreasonable to expect. And that these loans depend on these new fossil fuel extraction sites operating for decades. In other words, they argue that fossil fuels are a bubble waiting to pop.

According to the Rainforest Action Networks’ excellent work, from 2016 to 2020, big global banks loaned out $1.488 trillion for fossil fuel expansion, specifically earmarked to fund the exploration and extraction of new sites. Those loans only pay back if fossil fuel demand remains strong and prices remain high enough to make working such new sites profitable.

If something changes, say, demand for oil drops due to the rise in electric car ownership, the fossil fuel industry might experience a massive debt crisis. With sites unable to operate profitably, companies across the industry would be unable to pay back their loans, pushing ripples of bankruptcy into the economy.

How bad of a debt crisis could this be? To put it in perspective, the total value of subprime mortgages in March 2007 amounted to $1.3 trillion. Again, the big banks loaned out $1.488 trillion just for fossil fuel expansion from 2016 to 2020. The total loan was $3.8 trillion to fossil fuel companies. And that’s just the big banks. Governments and investors around the world are creditors to the fossil fuel industry.

There is a world where this bubble does not pop but slowly deflates. A gradual carbon tax sends enough of a signal to the investment market, and credit rating agencies can update the risk of fossil fuel loans in time. The fossil fuel industry has lived on "booms and busts" since its beginning. The problem here for fossil fuel investors is that a boom may not follow the next bust. Or that the boom may be much lower than before.

When a misalignment occurs between investor expectations and reality, the correction eventually comes. Zero-revenue tech stocks crashed in 2000. Subprime mortgages almost took down the financial industry in 2008. While these types of events bring down the investment world as a whole, they especially hurt those closest to the correction.

Investors are broadly not very good at long-term thinking, which is why we see bubbles pop instead of just deflating. While we cannot predict whether the fossil fuels bubble will pop or deflate slowly, we can estimate that those investors left holding the assets closest to the problem will incur the highest losses.

The fossil fuels industry is fundamentally in a long-term decline. It’s unclear whether Wall Street fully realizes that yet. But when it does, the damage could be severe, and those who looked ahead and chose to avoid owning fossil fuel equity, debt, and those of their creditors, will remain the most insulated from loss.

Investing in a Growing Industry

In general, it pays to invest in growing industries. The earlier the better.

If you had bought Apple right at the beginning of the digital music industry’s growth, on the date the first iPod was released (October 23, 2001) and held until the writing of this article (February, 14, 2020), you would have generated a 57,944.44% total return. That’s almost 580x your original investment.

If you had bought Apple on the date the first iPhone was released (June 29, 2007) and held until the writing of this article, you would have generated a 4476.55% return. That’s a very impressive ~45x increase. Obviously, Apple is in a class of its own as a company, but the point is illustrative. It pays to invest early in growing industries.

And many parts of the climate solutions industry are poised for significant growth over the next three decades, based on economics and regardless of government intervention.

Many of today’s ready-to-scale climate technologies make better business sense than their fossil-fuel counterparts. And many of tomorrow’s have equally high potential.

So let’s dig in. Where previously we walked through the growth rates these technologies require in the coming decades to keep the globe on track to avoiding 1.5ºC of warming, here we’ll go through what market researchers project those growth rates will actually be.

What Market Analysts Are Projecting for Climate Solutions Over the Next Five to Ten Years

If you look at the table below, you’ll see growth rates projected by the market research group Mordor Intelligence (yes, that’s their real name) for some of the major climate solutions technologies over the next five or so years. For reference (and to make this table much more interesting), we added the IEA’s growth projections for what we'd need from each industry over the next decade to be on track to avoiding 1.5ºC of warming.

|

Industry |

Timeframe |

What's Projected |

What's Needed (IEA) |

Timeframe |

|

Solar |

2019-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Wind |

2019-2026 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Energy Storage |

2019-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Electric Cars |

2018-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Heat pumps |

2018-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Bioenergy |

2016-2026 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Geothermal |

2019-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Green Hydrogen |

2020-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

Smartgrid |

2019-2027 |

2021-2030 |

||

|

CCUS |

2019-2027 |

2021-2030 |

The Strong Economic Tailwinds Behind Solar, Wind, Batteries, and Electric Cars

These technologies have a lot going for them. Across much of the world, solar and wind are now the two cheapest ways to generate electricity. Electric vehicles are cheaper to own over their lifetime and will soon cost less upfront than gas-powered ones. The rise of renewables and electric cars has significantly increased global demand for batteries, with the industry growing 77% per year from 2016 to 2020.

So while one should never rely too heavily on stock market projections like those of Mordor Intelligence, the projections are very likely directionally correct. These zero-emission technologies are just better than fossil-fuel technologies. Implementing them will save businesses and individuals money. Scaling them will make investors money.

And they are still at the beginning of their growth curves. Solar provided just 2.7% of global electricity in 2019. Wind provided 5.7%. Electric cars only represented 5.9% of all new car sales in 2021. The globe produced 631 GWh of battery cells in 2020. By 2030, McKinsey estimates we’ll be producing 2,912 GWh.

The Next Generation of Climate Solutions, Like Green Hydrogen, Have Significant Promise

And the next generation of climate tech has a similar promise. Let’s look at green hydrogen, the process of separating hydrogen atoms from water using renewable energy.

As we scale up solar and wind, there will be an energy excess on days with more sun or wind. Green hydrogen potentially enables us to make a liquid fuel to power transoceanic megaships, long-haul trucks, and even aircraft. And it would result from channeling a waste stream (curtailed electricity) into water.

To put such alchemy in perspective, imagine if a machine today could turn water into gasoline. And the energy used to power the machine was essentially free. How rich would the inventor of that machine be? How big of a return would the machine’s early investors earn? Extracting oil from the ground would almost immediately become an obsolete industry. This is the promise of green hydrogen. Except there’s no oil and no emissions. Just abundance.

Conclusion

Climate Solutions Poised for Growth & Any Type of Carbon Tax or Climate Legislation Makes Their Economics Even Better

Climate solutions are poised for significant growth without any sizable government intervention. With, say, a carbon tax, or the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, the economic advantages of climate solutions will become even more pronounced.

A price on carbon could provide a significant return on investment for those who invested in carbon capture and sequestration technologies.

Previous Chapter 02

Chapter 2: Why Your Retirement Fund Matters for Solving Climate ChangeNext Chapter 04

Chapter 4: The Current Sustainable Investing Landscape